Was Imam ʿAlī (a) a Misogynist? This is the title that Amina Inloes gave to her article about the phrases that have been “falsely attributed” to Imam ʿAlī in Nahj al-Balāghah that apparently undermine women. Aside from the rather crude and sensationalist title, the article aims to show that the statements in the Nahj where women are referred to as being deficient could not possibly have been uttered by the Master of Believers, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (‘a). From the melodramatic title, one can only conclude that anyone who disagrees with the author’s conclusions would have to accept that ʿAlī (‘a) was, god-forbid, a misogynist. This would be just like saying that the esteemed author of this article must be a misandrist because of her numerous works on women and implicit disregard for men!

Title aside, the article, which has been excerpted from a chapter of the author’s PhD thesis, aims to show that the passages which undermine women were late attributions that were falsely and posthumously imputed to the first Imam. She even speculates that these were Aristotelian tropes which somehow found their way into Islamic literature. A novel claim, but unconvincing and unsubstantiated. Inloes bases her arguments on what she terms a ‘detailed analysis of the textual sources’, followed by a critical examination of the various explanations and commentaries given by scholars for the specific passages of the Nahj, and finally a comparison between the so-called misogynist ideas in the Nahj and the approach taken in Kitāb Sulaym ibn Qays al-Hilālī.

We would take issue with each of these approaches. Firstly, what Inloes terms ‘a detailed textual analysis’ is lacking in many ways. She fails to examine the numerous traditions that are of similar or identical purport yet have been expressed in different wordings. This is a common problem with contemporary scholars who rely too much on digital resources and search for terms in large collections – they find select phrases but are unable to get other results of similar connotation because the phrases and words used therein differ. For example, we have a Prophetic tradition that has been narrated by the ‘Muḥammadūn’ in their important hadith collections that states:

مَا رَأَيْتُ مِنْ ضَعِيفَاتِ الدِّينِ وَ نَاقِصَاتِ الْعُقُولِ أَسْلَبَ لِذِي لُبٍّ مِنْكُنَّ

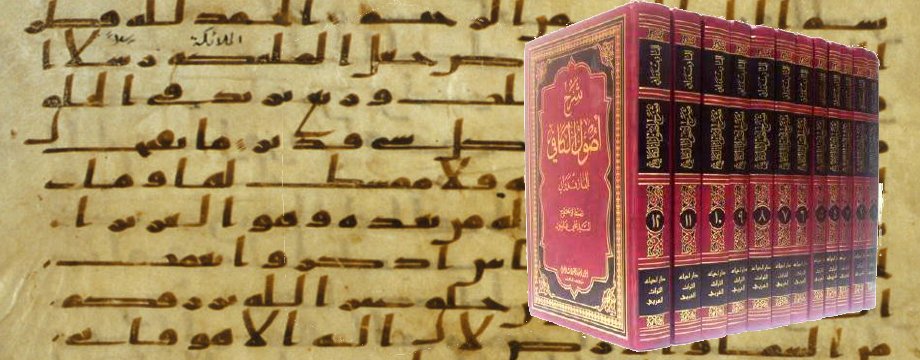

This has been narrated in al-Kāfī (5:322), Tahdhīb al-Aḥkām (7:404) and Man Lā Yaḥdhuruhu al-Faqīh (3:390), all of which are primary hadith collections. Moreover, there are numerous such traditions that have simply been overlooked. In fact, the sheer number of traditions would easily constitute tawātur maʿnawī regarding this issue, as some scholars have said. 1

Secondly, her critical examination of the explanations given by scholars is also unsatisfactory. She quotes Nasir Makarim Shirazi and then goes on to make a mockery of the views of other contemporary Shi’i scholars by making readers play a guessing game to see if they can tell whether the quotations she gives are from ancient Greek philosophers or contemporary Shi’i scholars. Alternative explanations and detailed studies on the subject have not been objectively examined and it seems the author had already decided that these passages are fabrications and is only trying to prove her case. This is despite the fact that centuries of scholarship and over 60 commentaries on the Nahj exist. One would have hoped for a more thorough examination of the same. In addition, recent articles like that of Masjidi have not even been mentioned.

Thirdly, Inloes tries to compare the passages of Nahj al-Balāghah with Kitāb Sulaym ibn Qays. She skirts round the subject of the latter’s authenticity and uses the views of only Western scholars, such as Hossein Modarressi, to show that it can still be used to show what people thought and felt during the early days of Islam. And of course, since there is no mention of such phrases in Sulaym’s work, they must be a forgery and later attributions. This is another poor argument, for even if we were to accept that the book of Sulaym that we currently possess is the real book written by Imam ʿAlī’s companion Sulaym ibn Qays, it would only show us Sulaym’s perspective on things and would not necessarily be representative of the views of the entire Muslim ummah. Furthermore, saying that ‘the early provenance of Sulaym’s book is evident from his views on women’ (p. 350) constitutes a cyclical argument. Are we basing the assumption of early provenance on his discussion on women or are we basing the general understanding of the status of women on its early provenance?

In conclusion, Inloes fails to prove her case in this article and while we appreciate the effort, we would caution the esteemed author against jumping to sweeping conclusions based on biases or preconceived feminist notions. With prayers for success and praise to the Almighty.

Notes:

- Haydar Masjidi, Nadhrah Jadīdah li Waṣf al-Nisāʾ bi Nawāqisi al-ʿUqūl, 2015 ↩